Potsherds - Ghost of Metabolic Relationship – End of a Long Day

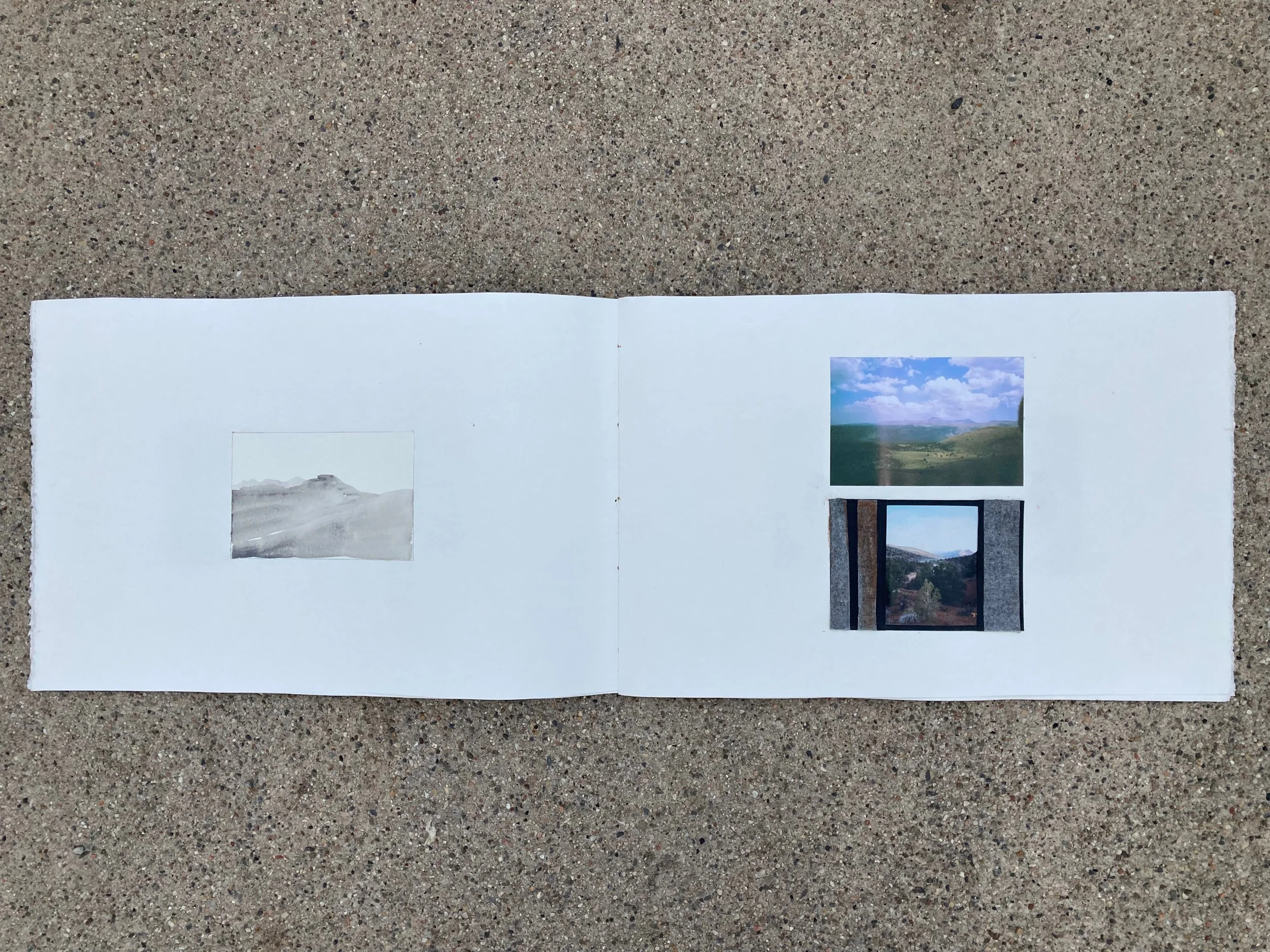

The Vermillion Cliffs still looked like a long way off. We continued through the piñon and juniper hills, stopping to take pictures and video whenever we passed another waypoint. We tried to reimagine the deer in the places she recently occupied. But the form of her ghost was uncertain. Was she alone? Was she with others?

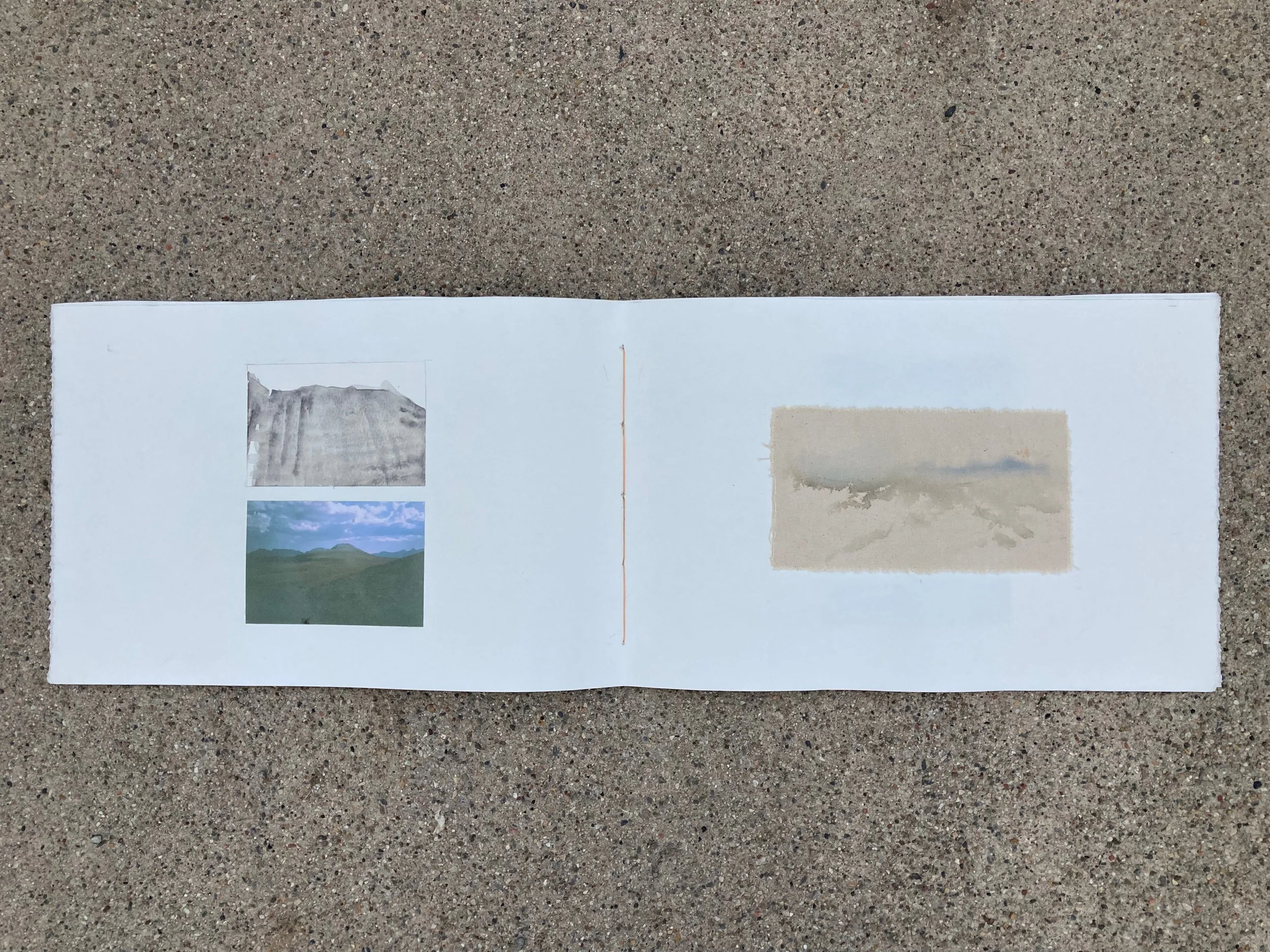

Soon we began finding potsherds. Some were black on red or black on white. There were corrugated rim pieces and even the very bottom of a pot. According to the GPS, the deer stood in this very spot about a month ago, browsing bitterbrush where people once resided. A new, overlapping story began to form out of the land.

Virgin Branch Ancestral Puebloan Culture occupied the area from about 1 CE to around 1200 CE. It has been an important migration corridor and mule deer and elk winter range for centuries, and that’s why people lived here. Mule deer were the dominant animal remains excavated from the nearby Dead Raven, Park Wash, and Kanab archaeological sites. Petroglyph panels feature deer prominently in nearby Johnson Canyon and Oak Canyon, as well, often with lines drawn from arrow tips to animal hearts. Knowing that this always was a mule deer migration corridor reveals a story whereby the Ancestral Puebloans dry farmed during the 190 or so frost-free days, and then hunted during the cooler months.

We dropped our packs and walked to the top of a hill from which the potsherds and pieces of chert seemed to emanate. Centuries ago, someone sat on this shaley hill leaning into the frail warmth of an early spring sun, pressing a piece of antler against a hunk of chert. Antlers are much stronger and more elastic than skeletal bone, making them ideal not only for knapping but also for weapon tips in some cultures. Tiny flakes cascaded down the hillside. Was the very animal whose heartline this rock would pierce the same animal who dropped his rack in a muddy, red wash that winter?

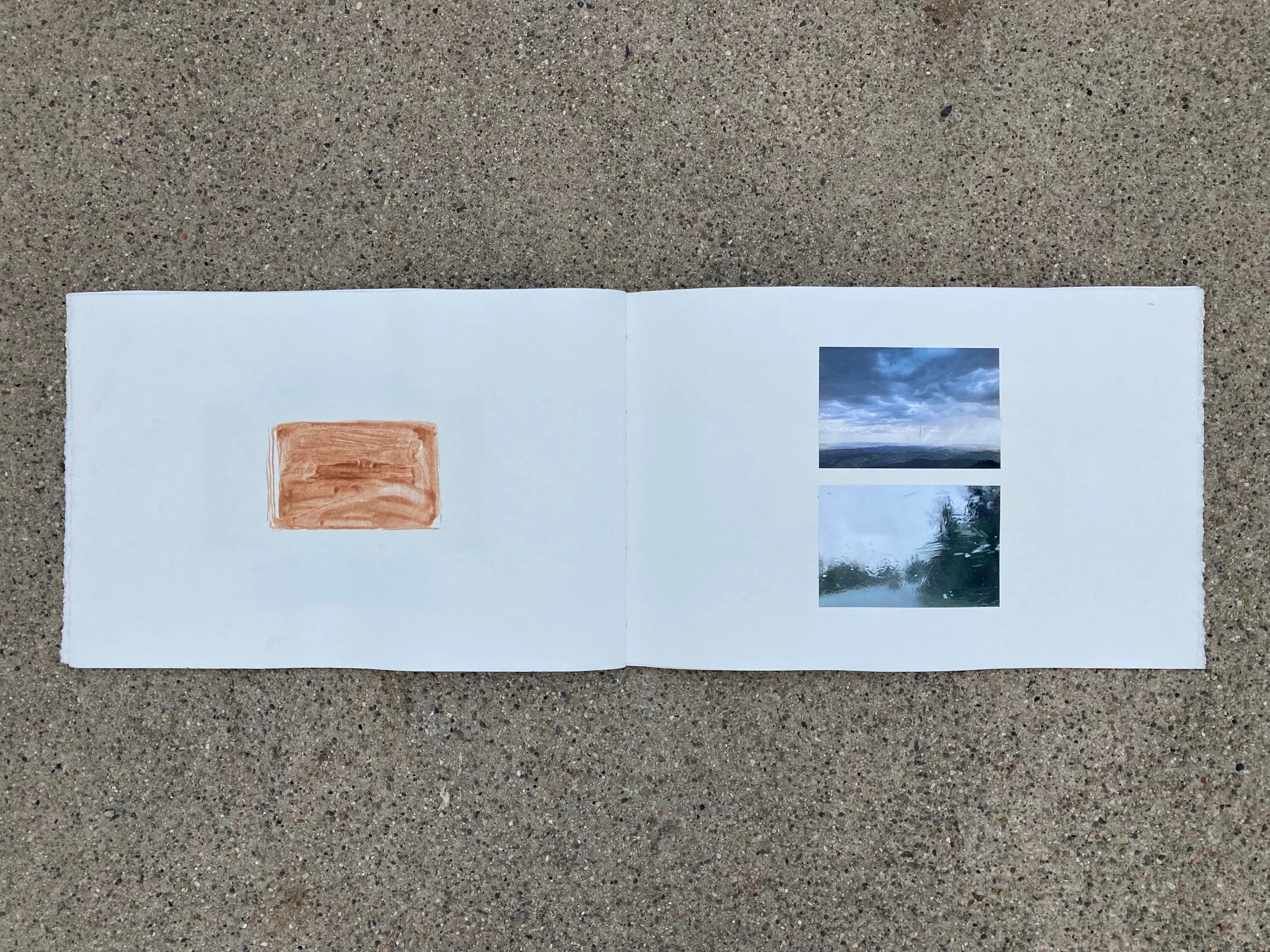

These artifacts revealed the link between animal movement and human subsistence. Today, because we are no longer reliant on seasonal animal movement, it is difficult to relate to migrations in the same way. The ghost of the metabolic relationship between human beings and deer haunts the land. In the absence of this relationship, cheat grass and russian thistle grow where I stood eating beef jerky out of a plastic bag. The ghost is not just the absence, but also what replaces it.

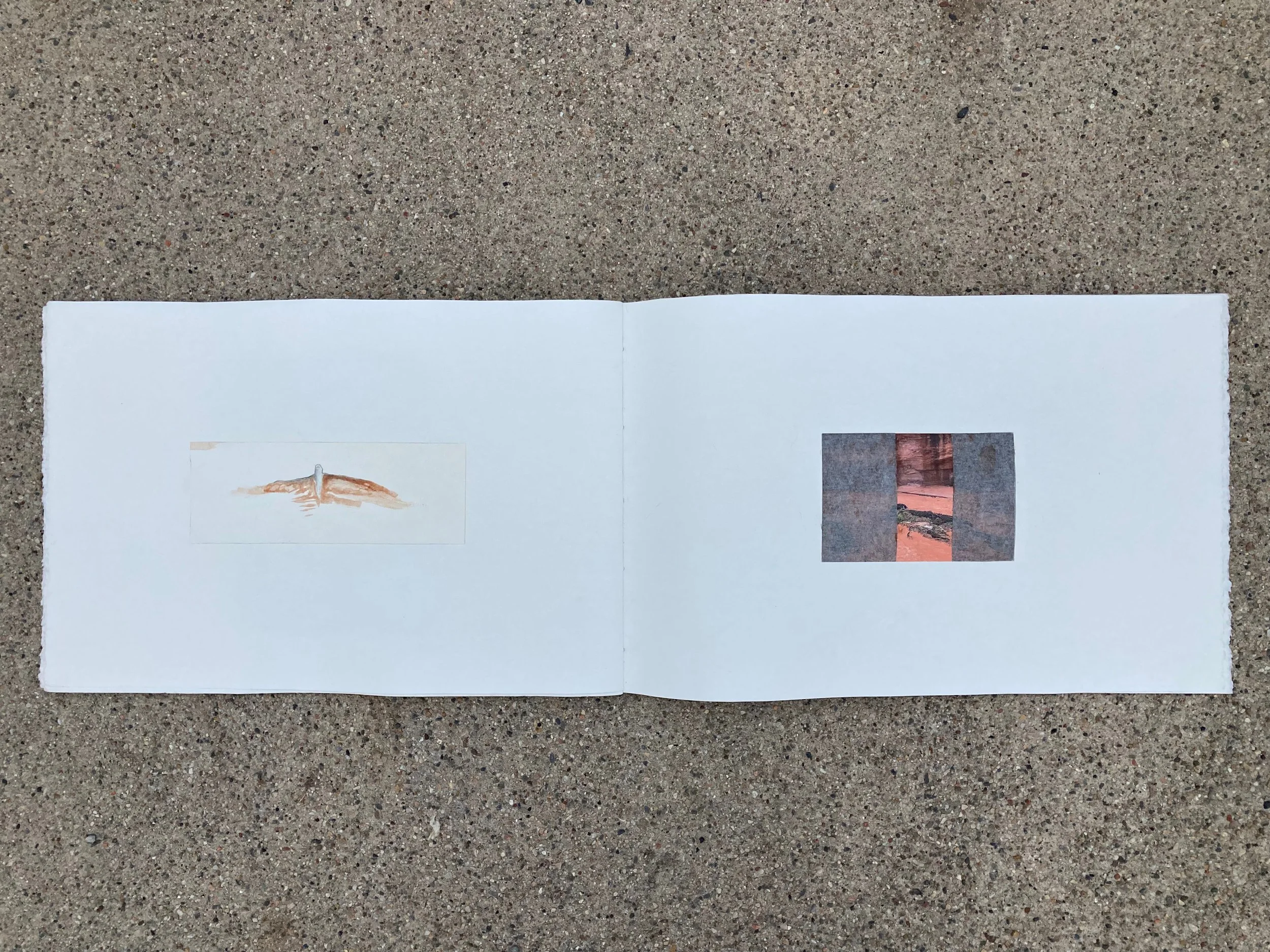

The movement of deer back and forth between winter and summer ranges transfers energy across landscapes. Deer and other native ungulates consume autotrophs, organisms that turn the sun’s energy into food for growth. This energy is then transformed into portable food—like deer—for other heterotrophs like mountain lions to consume. Energy is transferred in this way from Buckskin Mountain through the Grand Staircase, over the Pausaugunt Plateau, and across the Markagunt Plateau. Deer transform forbs, grasses, and shrubs into excrement, which they deposit across the landscape. And when a deer dies, the mobile energy stops. The body lies in the blazing heat where it seems no body should. It lies splayed out in the icy winds that rip across the Arizona Strip in January. The body, endeavoring for no shelter, displays the starkest absence of life. But spark absent, energy is not. Ravens and vultures pick at the body. A coyote tugs until a leg comes off and she carries it into the trees. Brown and gray open to pink and red. Pink and red open to white. This sort of blooming disperses energy through trophic systems far from the place where the deer was born. Pre-Columbian humans and wolves understood this transfer of energy and followed it, hoping to capture it in a form barely removed from life. Still warm. Mountain Lions follow, wait, follow, wait, follow, wait.

Today, cows absorb much of the autotrophic energy along this corridor, and they are then trucked elsewhere. They contribute little to the metabolism of the land. Predators are not allowed to touch them. Ravens, vultures, and bacteria might get lucky every once in a while and find a lost, drowned, or frozen cow.

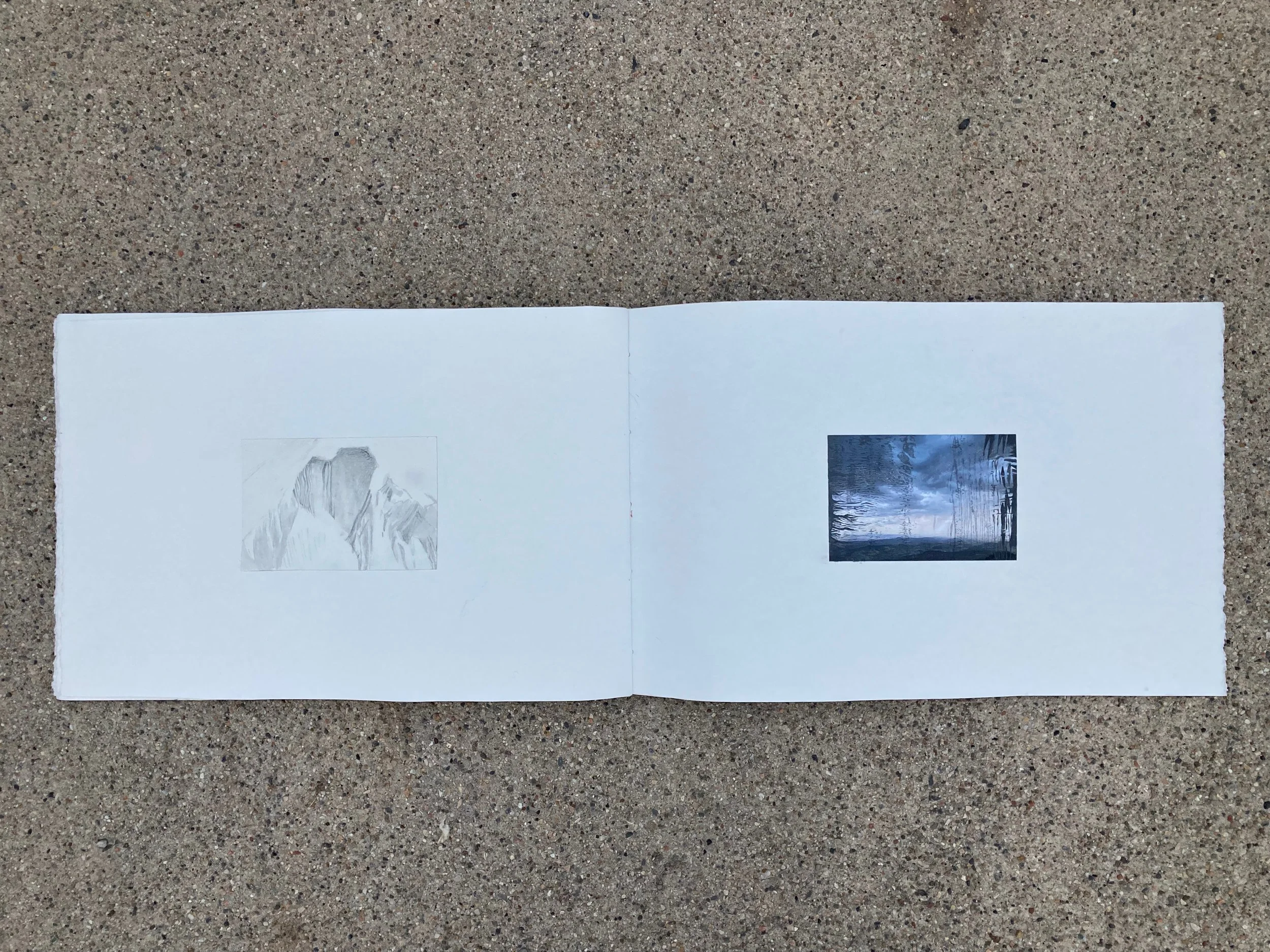

The path disappeared at the edge of the trees. Acres and acres of what was once forest spread out before us. On the screen of my phone she beelined to the next forested area. We deviated from her path at this point and took the road; we needed a break from bushwhacking. On both sides of the road, stumps and shredded limbs of junipers looked like sunbaked catacombs, and globemallow and pale green grasses rose up around them. I wondered if deer and elk once walked through this area, but have been relegated to the forest nearer the Vermillion Cliffs. Deer use piñon and juniper forests as both thermal and hiding cover. The deer we followed appeared to be avoiding cattle grazing areas because it was unsafe for both her and her soon-to-be-born fawn(s). A lack of cover due to the impacts of grazing can increase fawn mortality because it becomes more difficult to hide from predators. I began to see this generational signature of animal movement rewritten by road construction, cattle grazing, and the resulting piñon and juniper removal. As a signature was rewritten, ghosts were born. Absences of humans, deer, and mountain lions now haunt this juniper graveyard while Kentucky bluegrass catches the first light each day, and the cattle’s long, low bawls permeate the dawn.